Hard Choices in Designing Payment Systems

We’re back from a remarkable week in Cape Town for the second Global DPI Summit. The event brought together more than 800 participants from government, industry and civil society to discuss the future of digital public infrastructure.

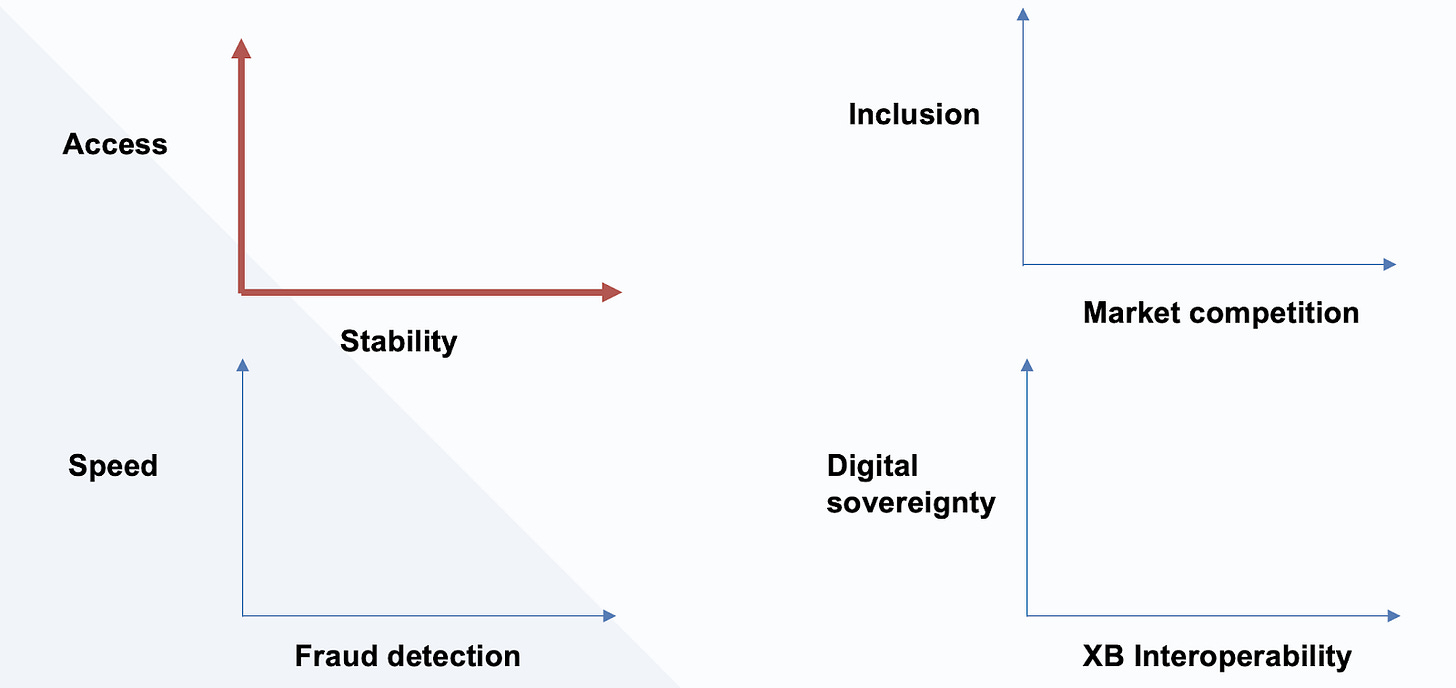

In our session on Day 2 of the Summit, we partnered with AfricaNenda to host an interactive session that explored the trade-offs involved in designing DPI payment systems. How do countries calibrate between promoting innovation and advancing financial inclusion? Between speed and trust? Between sovereignty and interoperability? We learned from participants from diverse geographies and institutional vantage points who helped map the contours of these dilemmas. In this post, we share some of the key takeaways from the conversation and connect them to current policy developments.

Setting The Context

First, it’s worth noting that the world of payment systems is filled with trade-offs. Historically, central banks have built and operated wholesale payment systems, which have always involved a fundamental tension between access and stability.

Take Fedwire, for example—the U.S. wholesale payment which settles transactions in central bank money directly on the books of the Fed. By design, access to Fedwire is restricted to institutions that maintain master accounts with the Fed. These are depository institutions—banks, credit unions, and savings associations—that fall within the regulatory perimeter of the Fed’s lender of last resort function and FDIC insurance. Left out of that perimeter are non-bank payment providers such as Venmo and PayPal. In other words, as Dan Awery notes, the settlement system of the world’s largest economy excludes many of the digital payment systems most widely used today.

Other countries have calibrated the trade-off between access and stability differently. In 2017, the Bank of England extended access to central bank settlement accounts to non-bank payment service providers (PSPs). The move was intended to promote competition in the payments space. But it also carries cybersecurity and liquidity risk. If one of the non-bank PSPs goes bankrupt, the central bank may suddenly find itself under pressure to backstop an institution it never intended to treat like a bank.

Three Trade-Offs

We discussed in our last post how the role of central banks within national payment infrastructures is evolving. Once relegated to the shadows of payment systems, central banks are now moving into the limelight, building out public payment rails for retail (not just wholesale) payments that exist toward the front end (not just the back end) of the payment chain. The framing question for our session at the DPI Summit: What new trade-offs must central bankers contend with as they step into this new role? And how should they navigate those trade-offs? Our conversation echoed what Edoardo Totolo, in a recent whitepaper, describes as the trilemma at the heart of DPI design: balancing public value, market dynamism, and systems integrity.

Market competition versus financial inclusion

The first trade-off that we explored in the session is market competition versus financial inclusion. Public payment rails that mandate low or no transaction fees promise to expand access to the formal financial sector. But when central banks act as market participants in the very markets that they are tasked with regulating, do they also unfairly stifle competition?

This is precisely the question at the heart of the Section 301 investigation into Brazil’s Pix launched recently by USTR. The U.S. argues that Pix gives the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) a privileged position in the payments market. By acting simultaneously as a regulator and operator, the U.S. contends, BCB disadvantages foreign card networks and fintech operators. Brazil, for its part, defends Pix as a non-discriminatory public good that has dramatically expanded financial inclusion.

One idea that emerged from our session: perhaps the goals of inclusion and competition stand not so much in tension as in sequence. Even in the case of private payment systems, competition often emerges as an important policy goal only after the platform has achieved scale. This is the story of Kenya’s financial regulators mandating mobile money interoperability in 2018 or China mandating interoperability between Alipay and WeChat Pay. In the case of public payment rails such as India’s UPI or Brazil’s Pix, we might assume an industrial policy logic, whereby the state supports an infant payments industry until it reaches maturity, then gradually opens the market to competition, including from foreign companies.

Finally, it’s important to distinguish between competition at different points in the payment chain. Public payment rails may stifle innovation and competition at the infrastructure layer, while also sparking competition further downstream—among the fintech players building apps on interoperable payment rails. This begs the question: Which kind of innovation matters most? The kind that happens within the core infrastructure or the kind that flourishes because of it?

Speed versus fraud detection

Recently uncovered internal documents reveal that Meta projects that 10% of its annual revenue will come from fraudulent ads, and that users are exposed to 15 billion ads for scams every day. Fraud is a pervasive issue across the digital economy and a particularly thorny challenge for governments building out digital public infrastructure in payments, identity, and data exchange.

This was the second tension we explored in our session: the trade-off between speed and fraud detection. Fast payment systems that settle transactions instantly and irrevocably offer convenience, but they also provide opportunities for nefarious actors. The problem is likely to intensify in a world of agentic AI, where automated tools will make deception faster, cheaper, and harder to detect. Which begs the question: How fast is too fast?

One participant offered a succinct answer: “when speed exceeds need.” Not every transaction needs to be instant. Often, routine payments such as utilities or social transfers can tolerate delay. Building in a measure of friction by design gives time for machine-learning systems or human operators to flag anomalies, and for users to retract mistaken or fraudulent transactions before they become irreversible.

But real-time fraud monitoring and online dispute resolution all require expensive infrastructure. As one participant noted, the real trade-off may not be speed versus fraud but rather cost versus fraud. Building safer systems costs money. Is the public sector prepared to shoulder that expense? And is the public prepared to accept the level of data visibility that robust fraud-detection mechanisms inevitably require?

Digital sovereignty versus cross-border interoperability

Central banks are not only building retail payment systems for domestic use; increasingly, they are embedding cross-border functionalities into their design. From a financial inclusion perspective, cross-border payments represent one of the most promising applications of digital public infrastructure, especially given how high remittance fees remain across much of the world. But cross-border interoperability, too, comes at the cost of local control and digital sovereignty.

This tension is playing out vividly today in the East African Community (EAC), where a new regional payments masterplan aims to connect the bloc’s eight member countries through a common payment system. The EAC initiative seeks to harmonize regulations and settlement frameworks across its members, but doing so inevitably involves ceding a measure of domestic control in the interest of regional efficiency and trade integration.

The tension between sovereignty and interoperability is not new or unique to payments. One participant drew an instructive analogy to NATO, where interoperability depended on a dominant actor—the United States, in that case—setting the standard. The challenge for regional payment systems like the EAC’s will be to achieve interoperability organically, through shared governance rather than imposed hierarchy.

To Build Versus To Buy?

Hovering over all of these trade-offs is a critical question of approach. For central banks exploring public retail payment systems, how should they go about building them? Broadly speaking, there are three paths: adopting open-source software (such as Mojaloop’s), contracting a private vendor—with the attendant risk of vendor lock-in—or developing proprietary infrastructure in-house.

This is often the first and most consequential policy choice that central bankers face. It sets the technical and institutional path dependencies for every other trade-off discussed above, shaping how systems balance innovation, inclusion, and sovereignty. It was also one of the major themes of the Summit as a whole. Increasingly, hyperscalers are entering the digital public infrastructure space, offering “DPI-in-a-box” solutions for governments seeking to build national systems quickly. But should countries rely on these private vendors to develop critical state infrastructure? At its core, this is not just a technical decision but a political one: who gets to shape the digital foundations of the national economy?